It’s a strange film, “Manifesto“, conceived and created by the artist Julian Rosefeldt.

It’s an ambiguous film, which plays with the concept of the manifesto (artistic and political): the manifesto is, naturally, something definite, clear; but the German artist gives a plural reconstruction of the manifesto, in a multiform and almost confused way.

He created a sort of Manifesto of the plurality of things (about art and the whole world), derived from the representation of a summation of singularities, a sum of Manifestos.

What is “Manifesto“?

Born as a video installation, the work consists of a prologue of 8′ and 12 mini-films independent one from each other, lasting 10′ 30 ” each.

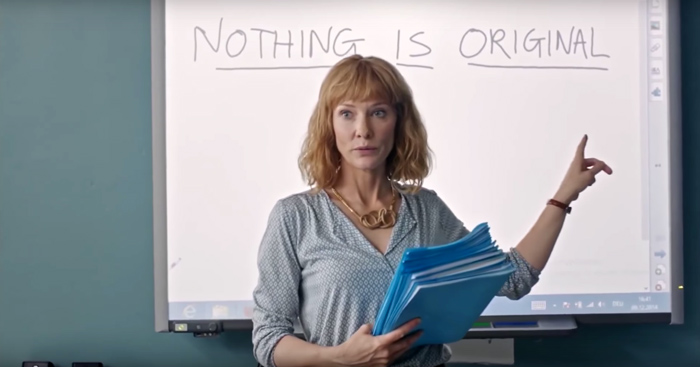

In each of these 12 mini movies, Cate Blanchett plays a character during a moment of his/her life. In each piece there is a different character, a different situation, caught in the middle of everyday life.

There is a clochard who walks, alone, among the remains of a disused industrial plant, and who screams against the world. There is a woman (perhaps the widow) who holds a funeral oration before the coffin is buried. There is a middle-aged woman who lives with her child and who has to juggle every day to survive. There is a CEO who welcomes and thanks her guests (probably her donors and sponsors) during a private party that seems like the opening of an art exhibition.

In each of these pieces is presented, to say it in this way, an artistic current of the XX century, through the words of its own manifesto. The manifestos’ words can be read by the voiceover or spoken by the character played by Cate Blanchett.

In the installation the various videos are projected simultaneously, highlighting the plurality of the work. In the movie, that has been drawn from the installation, the sense of plurality is made through the editing, which alternates the moments taken from the various mini-films.

The theme: Manifesto (or the Manifestos)

A manifesto is a stance. It is a text that represents a singular way of seeing the art world and therefore the world. In each manifesto a series of rules and principles are enunciated, and they will be followed, in the production of their works of art, by the artists who refer to the manifesto itself.

A manifesto is a way of simplifying the world: it often condemns and wants to eliminate some aspects of the world that don’t agree the ideas expressed. The manifesto introduces a new way of doing things, a new way of conceiving the world and art.

Basically, the manifestos are mutually exclusive.

Either you are a Dadaist, or you are Situationist. Either you are a Futurist or you prefer Pop Art. Or Expressionism or Minimalism.

So what is the meaning of a work, “Manifesto”, so plural?

How is this plurality connected to objects, like the manifestos, which preach, by their own nature, singularity?

“Manifesto” is not a documentary. The complete absence (in the representation) of every historical reference unequivocally bears witness to it.

Instead, we could read “Manifesto” as a document of the plurality of artistic initiatives of the last century (such a case history).

This is to underline how Art, in absolute, is a path in continuous becoming, that never stops, not even when trying to put firm points, just as the manifestos should do.

The decision to insert the various “citations” from the various manifestos within contexts extrapolated from the many corners of contemporary everyday life, establishes new connections between the texts and the images, between the texts and the stories presented.

The quotes from the Dada manifesto, then, pronounced during the funeral oration, can be linked to the Dadaists’ desire to “bury” the art as it was, in order to open a new season.

Or the long prayer before lunch, which the affluent lady pronounces before a laid table, in front of her husband and her children, may seem strident with the words for a POP Art by Claes Oldenburg (from “I am for an Art …”).

Or again, the instructions of Dogme 95, by Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg, can be almost ridiculous when they are enunciated in chorus by a teacher and her class, as if they were the principles of the Constitution of a Nation or of the religious commandments.

It is this exactly eternal alternation of ideas, as well as of lives and situations in life, probably, that the work of Julian Rosefeldt wants to highlight.

Everything changes, always, in art as in life.

Each manifesto would/should indicate the only way. But their bundling instead, does nothing but demonstrate the exact opposite, that is the unquestionable (post-modern) plurality of the world.

Images courtesy of Julian Rosefeldt

Text by Domenico Fallacara | the PhotoPhore

Discover: www.julianrosefeldt.com