The Body Extended: Sculpture and Prosthetics at the Henry Moore Institute (Leeds) traces how artists have addressed radical changes to the very thing we humans know best: our bodies. Presenting over seventy artworks, objects and images spanning the late-nineteenth century to the present day, this exhibition explores how sculpture and medical science have augmented the analogue human figure, expanding its reach and power.

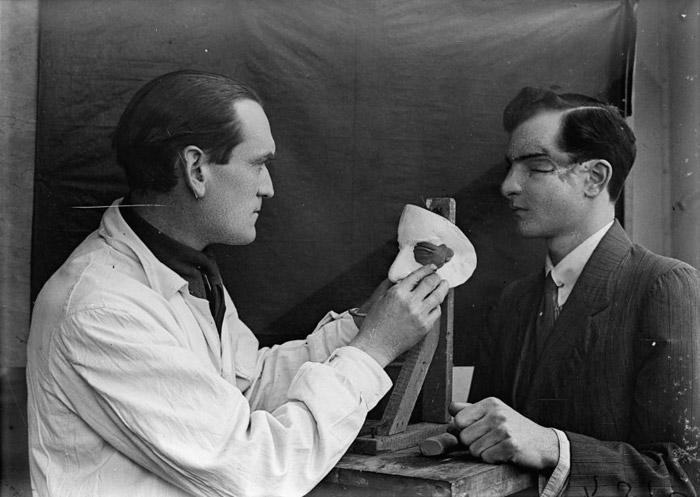

Captain Francis Derwent Wood RA of the Royal Army Medical Corps holds an artist’s palette as he adds the finishing touches to a patient’s new facial plate. Photo by Horace Nicholls, c1914–8

Captain Francis Derwent Wood RA of the Royal Army Medical Corps holds an artist’s palette as he adds the finishing touches to a patient’s new facial plate. Photo by Horace Nicholls, c1914–8

Painted metal facial prosthesis attributed to Anna Coleman Ladd (1878-1939), made in France, 1917-1920. Courtesy of the Antony Wallace Archives of the British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons

Painted metal facial prosthesis attributed to Anna Coleman Ladd (1878-1939), made in France, 1917-1920. Courtesy of the Antony Wallace Archives of the British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons

Outside the Henry Moore Institute, on the city’s busiest thoroughfare, is a sculpture made for the exhibition by British artist Rebecca Warren, co-commissioned with 14-18 NOW: WW1 Centenary Art Commissions. As the artist describes the work, it is a weighty, raw bronze sculpture, mainly of legs made of extreme convexities of muscle, set on a rudimentary bronze wheeled platform, taking (or showing) one monumental stride.

Matthew Barney, The Cabinet of Bessie Gilmore, 1999. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

Matthew Barney, The Cabinet of Bessie Gilmore, 1999. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

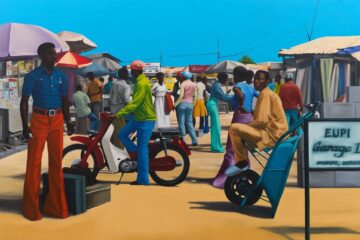

During the First World War prosthetics technology rapidly advanced. As shattered soldiers became a familiar sight in public life after 1914, both artists and surgeons alike sought to remake what had been lost. Sculptors Anna Coleman Ladd and Francis Derwent Wood worked directly with surgeons, creating facial masks for soldiers injured in the trenches, with show’s display presenting two examples of these, while in contrast artists including Alice Lex-Nerlinger and Jacob Epstein show the horrors of the new machine-human.

Rebecca Horn, Finger Gloves, 1972. Photograph: AchimThode. Courtesy of Rebecca Horn / DACS, 2016

Rebecca Horn, Finger Gloves, 1972. Photograph: AchimThode. Courtesy of Rebecca Horn / DACS, 2016

Alongside examples of prostheses from the collections of the Freud Museum, Hunterian Museum, Imperial War Museum, Thackray Medical Museum in Leeds and the V&A, “The Body Extended: Sculpture and Prosthetics” features work by artists who directly address the relationship between sculpture and prosthetics. Prostheses recur in the life and work of Louise Bourgeois, with her work drawing on her own experiences and childhood traumas. A single leg (1985), named after Bourgeois’ sister Henriette, is suspended in space surrounded by the body extensions of Rebecca Horn, Matthew Barney and Oskar Schlemmer, among others.

Heinrich Hoerle, Denkmal der unbekanntenProthesen (Monument to Unknown Prostheses), 1930. Courtesy of Medienzentrum, Antje Zeis-Loi / Von der Heydt-Museum Wuppertal

Heinrich Hoerle, Denkmal der unbekanntenProthesen (Monument to Unknown Prostheses), 1930. Courtesy of Medienzentrum, Antje Zeis-Loi / Von der Heydt-Museum Wuppertal

The Body Extended: Sculpture and Prosthetics

21.07.2016 – 23.10.2016

Image 1: Stuart Brisley, Louise Bourgeois’ Leg, 2002. Photo: Andy Keate. Courtesy of the artist and Hales London, New York

Discover: www.henry-moore.org